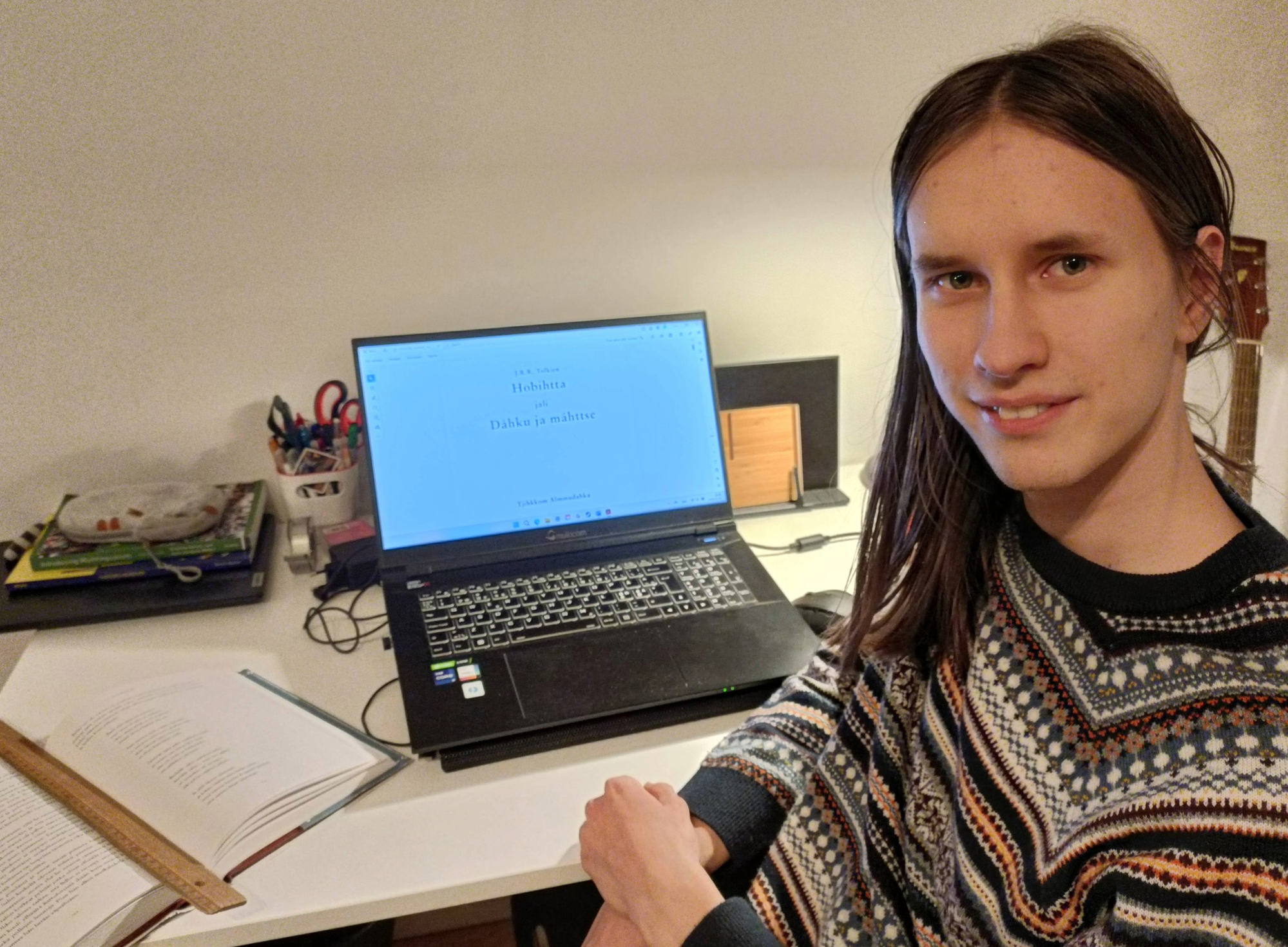

Are Tjihkkom – Translator of the Month

Our translator of the month for December is Are Tjihkkom, who translates fiction into Sámi. He works primarily from English, but he has also produced translations from Norwegian, Swedish, German, Finnish and Spanish. His main focus is on books for adult readers, but he tries to work on a variety of material from numerous sub-genres, including fantasy, comedy and science fiction. Are established his own publishing house in 2020 through which he publishes his translations, and has so far released nine titles, with the tenth underway. His mother tongues are Sámi and Finnish, and he uses the written language of Lule Sámi in his translations.

How did you end up translating Norwegian literature into Lule Sámi?

I grew up with very little Sámi literature. There were only a handful of books available that everyone in my generation (and the generation before me) has read, and new releases were few and far between. I’ve heard people talk about the ‘Sámi agony’ of being required to read certain books regardless of whether you like them or not, just in order to be able to read something in Sámi. That’s less true nowadays than it once was, but there is no reliable producer of literature in Lule Sámi, meaning that books are still in chronically short supply. The need to translate books stemmed from the fact that there is no system that enables translation as predictable and steady work, so I took it upon myself, following in the footsteps of many language workers and translators before me.

Working with languages is good fun.

When it comes to Norwegian literature, I’ve only translated a few children’s books and Knut Hamsun’s Pan, so it’s not something I’ve attached a great deal of importance to, but it all depends on demand and what I happen to stumble across. When it comes to Hamsun, I translated Pan because I’d worked on a few excerpts from the book for The Hamsun Centre in Hamarøy, the municipality I come from. It seemed a shame just to have a few extracts lying around, so I decided to work on the rest. On other occasions I work on books that I’m already familiar with, or books I’m recommended to look into. It’s thanks to chance as much as anything else that I’ve ended up translating from Norwegian.

Your Finnish colleague, Kaija Anttonen, passed the Translator of the Month baton to you:

You’ve translated an incredible number of books into Lule Sámi from a range of fictional genres, including work by Knut Hamsun, Grete Haagenrud, Lewis Carroll, J. R. R. Tolkien and Gabriel Garcia Márquez, not to mention short stories by Edgar Allan Poe, Anton Chekhov, Leo Tolstoy, James Joyce, Aleksis Kivi and Virginia Woolf, among others. Whilst working on Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, you collaborated with others more intensively than translators tend to do. There were undoubtedly many words in the book that required you to come up with your own new words in Lule Sámi. Could you tell us a little about this model of collaborative translation and whether you used the same method when you translated Tolkien’s The Hobbit?

It goes without saying that when it comes to Sámi, a ‘young’ written language standardised in the 1980s with very little variety across the genres, a huge number of words and expressions lack good, well-established equivalents I can use in translation.

There are various methods for creating words, each with their own advantages and disadvantages. Loan words are fairly simple, for instance, you simply adapt the source language. That approach can be sensitive from a language policy perspective, though, since a degree of linguistic purism is favoured when it comes to Sámi. Loan words often face opposition. I tend to focus on comprehension; I’m currently translating a book from English that features the word ‘stylist’, for example. There’s no point in trying to come up with an equivalent for such a well-established word that everyone understands, so it’s easier just to write it with the pronunciation adapted, which becomes stájlissta. It’s important to work with readers to see how they pronounce what they’re reading, and whether they understand the meaning. These aren’t officially standardised words or spellings, so it’s important to consult others.

Just like any language, Sámi has lots of options when it comes to developing new words from existing ones. Particularly when there is no real sense of agreement in place, a new word can offer a solution, like starting with a blank slate. Speakers can use different source languages for loan words, meaning that a word used by Sámi speakers in Norway may not be immediately recognised by those in Sweden, because Norwegian and Swedish use different words to describe the same thing. This is the case when it comes to ‘computer’, for example, which is datamaskin in Norwegian and dator in Swedish. I’ve used dáhtámasjijnna (which I personally use), datåvrrå, dihtur and others, all to describe the same piece of equipment, and it is difficult to choose one written form without any sense of agreement. It’s not enough for me simply to use the words I happen to use myself, because I’m not the person that I’m translating for. My consultant and I ended up using a word for understanding, buojkkát, and after some further work we landed on buojkáldahka as a translation for computer, which describes something that explains, or a tool to aid understanding.

Lewis Carroll’s language was particularly good fun to work with from a linguistic perspective, because I had to translate nonsense to nonsense. I spent quite a bit of time reading about the origins of these words in English and talking to others about what equivalent ‘nonsense’ might sound like in Sámi. Without getting into things too deeply, Jabberwocky became Sjoados, gyre and gimble became girrin ja guorrádin, and brillig became máleldis. These aren’t actual words but new creations, for the most part. Taking the latter as an example, máleldis comes from máles, food or a meal, which I combined with idedis, the word for morning, putting them together in an unorthodox way much like the original.

Three of Are’s translations into Lule Sámi are from Norwegian. Most of his translations – so far nine in total – are published by his own publishing house, Tjihkkom Almmudahka.

Do you have a favourite word – or a nightmare one, perhaps?

Samboer (the Norwegian word for a long-term, live-in partner) leaves me stumped! It’s often used in Norwegian and captures a certain type of relationship in a very precise way without sounding clumsy or overly formal. I sometimes find myself impressed and infuriated by how difficult some words can be to translate. No matter how I rephrase things or try to spin them in Sámi, I can’t come up with equally elegant equivalents in translation.

Read more

Learn more about Are on Books from Norway.

See also his translations from other languages, here (list in Norwegian only).

See the Facebook-profile of his publishing house, Tjihkkom Almmudahka, here.

Those of you who understand Norwegian can read his interview in full here.

See also other translators interviewed in the Translator of the Month series.