Guy Puzey - Translator of the Month

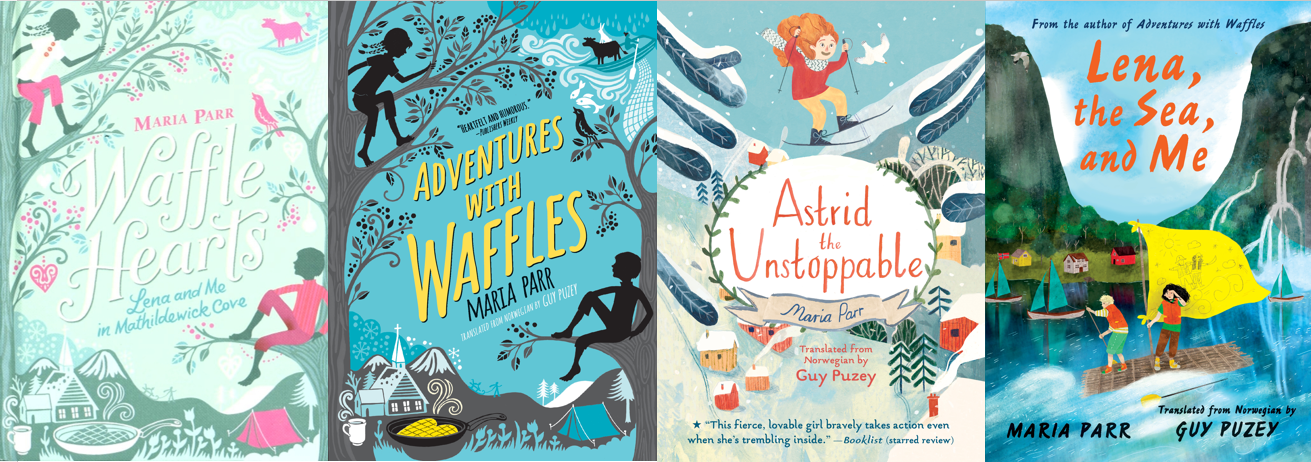

Our translator of the month for March is Guy Puzey from Scotland. Guy works in Scandinavian Studies at the University of Edinburgh, where he is also currently Head of the Department of European Languages and Cultures. He has translated work by a wide range of authors, especially from Nynorsk, the lesser-used of the two official written standards of Norwegian. He was shortlisted for the 2015 Marsh Award for Children’s Literature in Translation for Waffle Hearts (published in North America as Adventures with Waffles), his translation of Maria Parr’s Vaffelhjarte.

How did you start translating Norwegian literature?

My high school was by the shores of Loch Ness, and although it was a small school, I was extremely lucky to be able to study three languages: French, German, and Italian. The fact some Italian was offered was thanks to the multi-talented German teacher. Her husband happened to be Sardinian, and in my last year at school, I took on a job cleaning the classrooms at the end of each day, working alongside this brilliant and generous man, Battistino, who also gave me Italian lessons. All this happened at the same time I had made the acquaintance of a girl in Italy, whom I am now married to, and we had met through a mutual interest in Norwegian music. So it seemed the obvious thing to continue studying Italian and combine it with Norwegian too, which I was able to do at the University of Edinburgh.

One of my favourite courses there was the final-year course in translation from Danish, Norwegian and Swedish. It was taught by Peter Graves, a distinguished translator and specialist in Swedish. There was something I found deeply satisfying in taking a text from one language, disassembling it, and then recreating it in another, possibly in quite a different shape, all while trying to keep the essential message and tone intact. The main catalyst for getting into translation professionally came from Kari Dickson, who was another one of my tutors and is an eminent translator of Norwegian.

As my contacts grew in the Norwegian publishing world – with the support of NORLA among others – I took on more sample translations and eventually whole books too. My first full-length translation was of Øyne i Gaza (Eyes in Gaza) by Mads Gilbert and Erik Fosse, which I co-translated with Frank Stewart, who also happened to have studied Italian and Norwegian in Edinburgh.

Do you do any other work apart from translation, and if so, what?

I work full-time as a lecturer in Scandinavian Studies at the University of Edinburgh, so I’m involved in teaching Norwegian language, Scandinavian literature, Nordic society and cultural history, and translation from Danish, Norwegian and Swedish. My job also involves research, including practice-based research on literary translation, sociolinguistics with a particular focus on the relationship between language and power, and work on the social and cultural history of Nordic-Scottish relations. Right now I’m also Head of the Department of European Languages and Cultures, which is Scotland’s largest university department of modern languages, so that gives me plenty to do!

Your Dutch colleagues, Kim Snoeijing and Lucy Pijttersen, had the following question for you:

We met Guy in 2014 at the translators’ conference in Asker (he might not remember us!).

Guy gave a talk on how to translate Norwegian swear words and other expletives. This is a major quandary, as if a Norwegian book has a great deal of swearing, that doesn’t necessarily mean that a (Dutch) translator can swear just as much as the Norwegian author. Sometimes the Dutch publisher won’t accept it. Besides, many Norwegian swear words are connected to the devil, while in the Netherlands – and perhaps in other countries – they are more often linked to God (or to illnesses).

We remember Guy saying that he never personally swore: when he was asked to give that talk, he didn’t say ‘s**t’, but maybe just thought ‘oh dear’! We hope we remember that correctly.

Our question to Guy is:

‘Hi Guy! What do you do when a publisher asks you to cut most of the swearing from a translation you’ve done? Do you try to find less offensive words, or do you remove them altogether? Have you got any tips?’

Hello, Kim and Lucy, and how lovely to hear from you! I haven’t really experienced a publisher necessarily wanting to remove swearing from a book altogether, but I agree there is a substantial job of cultural and linguistic calibration to be done every time a translator encounters swearing, or something that resembles it. I would say the most crucial thing is to think about the emotive power these words have.

A book that presented some swearing challenges was Arild Stavrum’s football-themed crime novel Golden Boys (Exposed at the Back). One chapter features a lively piece of television commentary by a character from Tromsø in northern Norway. These pages were the most exciting to translate in the book: not only was the dialogue in northern Norwegian dialect, but it was also peppered with extended outbursts of highly vivid and creative swearing. The situation is made especially comical by the fact that it’s all happening live on television on a Sunday afternoon, but for many readers on this side of the North Sea it’s pretty unbelievable that somebody could swear so much on live television without being stopped and without losing their job, as offensive language in television and radio broadcasts is quite strictly regulated compared to Norway. So I felt it was necessary to tone down the language a little for believability, and to highlight the comical side of it. Nonetheless an editor with that book must have thought it wasn’t that problematic to swear on live television, as some swear words were actually made stronger in the edit!

What about children’s books?

I greatly enjoyed translating Maria Parr’s three children’s novels Vaffelhjarte (Waffle Hearts / Adventures with Waffles), Tonje Glimmerdal (Astrid the Unstoppable) and Keeperen og havet (Lena, the Sea and Me).

Maria generally avoids swearing in her writing, but one of the distinctive features of all three books is the use of inventive pseudo-swearing or minced oaths. These are euphemisms or humorous substitutes for swear words. Parr uses many unusual examples of these, some of which are idiosyncratic creations found only in her works, and her readers love them. So what to do with them in English?

With the first book, I felt a need to enhance the sense of place for the setting in a small coastal community in western Norway, and one way of doing this was to opt for a fish-related theme in translating the minced oaths. For example, the protagonist Lena’s catchphrase ‘søren ta’ became ‘smoking haddocks’ or ‘you smoked haddock’, depending on context, while another character’s ‘honden-dondre’ became ‘suffering sticklebacks’. The second book featured a different setting and new characters who were more connected to the mountains and glens than to the waves, so this time I took inspiration from terrestrial flora and fauna, with new expressions such as ‘blinking badgers’. In the third book, we were back to the same coastal setting as before and with more of these phrases than ever, so once again I trawled the sea (metaphorically) to find suitable terms. Some of them are quite widely used in English already, such as ‘holy mackerel’ or ‘fishcakes’, but others are a bit more unusual, such as ‘Jiminy Monkfish’ or ‘son of a sea bass’.

You’ve worked in various literary genres including children’s books, fiction and non-fiction. Is there a genre you wish you could work with (or work with more) in the future?

I’m delighted to work with a broad range of genres. I do think literature for children and young adults in Norway is particularly innovative, including the quirky work of illustrators such as Gry Moursund and Per Dybvig, so I would like to see more of these books making their way from Norwegian into English. As a reader of bedtime stories to my two-year-old son, I confess I might have an ulterior motive.

I am also very keen on promoting minority or lesser-used languages. This is one of the reasons I have specialised in Nynorsk, and I would love to be able to translate some of the other languages of Norway, especially Sámi languages. Unfortunately I’m not aware of any Sámi language courses in Scotland, but I have been collecting resources for North Sámi in the hope that I will have enough time for it in the years ahead.

What would you be if you weren’t a translator?

I have had many alternate-universe ambitions, but I am what you might call an aviation enthusiast, so when I was a child the dynamism of a career as a pilot appealed to me most of all. My eyesight was too bad for any type of job in the military though, and I couldn’t have afforded commercial pilot training. I also loved physics and everything to do with space, so I thought about becoming an astrophysicist, but then I met a charming girl from Italy, as mentioned above, and suddenly I realised that language learning could also be used to make new friends and expand horizons. Translating Norwegian and all the things I do in my university job let me keep doing that, while hopefully helping some other people to expand their horizons too! With hindsight, I now feel quite grateful that I wear glasses.

Is there any particular Norwegian book that’s close to your heart? If so, what makes it so special?

I am a big fan of Loe’s originality and subtle humour, and Muleum is a book that has stayed with me for a long time. It tells the story of Julie, an eighteen-year-old girl whose parents and brother are killed in an aircraft accident. The novel follows Julie’s diary as she struggles with bereavement and dark thoughts. She tries to live dangerously and hopes she might die in a crash too, but by the end of the book, Julie is full of a determination to live. With the current rise in mental health awareness among young people, I wonder if this novel could find real therapeutic applications. It deals unusually well with tough and potentially awkward themes, treating them carefully but with a major dose of (occasionally dark) humour. It isn’t really sarcasm but self-irony as a way of gaining perspective on depression. I see the book as empowering and strangely hopeful.

We hope you’re ready to pass the baton to a colleague who also translates from Norwegian. Who would you like us to hand off to, and what would you like to ask them?

I would like to pass the baton to my good friend Ioana-Andreea Mureșan. We first met at the International Summer School at the University of Oslo in 2005. Ioana translated the first and fifth books in Karl Ove Knausgård’s series My Struggle (Min kamp) into Romanian, and I believe she did this alongside an assortment of other work commitments, which is a situation familiar to many translators. I’d like to ask Ioana if she has any tips she can share from her experiences that might help the rest of us translators plan our time wisely!

Read more

Those of you who understand Norwegian can read Guy’s Translators of the Month interview here

Learn more about Guy on Books from Norway

We also recommend an article Guy has written for the British Council:

‘Profoundly democratic’: learning Norwegian as a foreign language

Other translators interviewed in our Translator of the Month series